Amy Ernst trained and volunteered as a rape crisis counselor in Chicago before deciding that she would move to the Democratic Republic of Congo to see how she could help victims of sexual violence.

Amy Ernst trained and volunteered as a rape crisis counselor in Chicago before deciding that she would move to the Democratic Republic of Congo to see how she could help victims of sexual violence.

She’s currently working in North Kivu with COPERMA, a local organization that has started ten centers for rape victims, demobilized child-soldiers, and displaced children and families.

I learned about Amy when I read her guest blog in Nicholas D. Kristof’s column in the New York Times. She described there the horrendous sexual violence against women and children in the Congo. Her raw determination to help the people affected by war was apparent.

I wanted to find out what persuaded her to relocate to this unsettling chaos. What did she hope to accomplish in a place that’s been called “the rape capital of the world?”

“I have never in my entire life understood the strength of humanity as much, and more specifically, the strength of women, as I do here…”

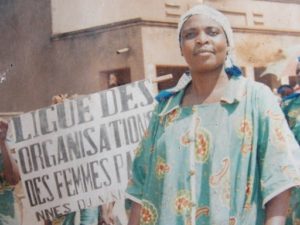

The photos on this post are the property of Amy Ernst. You can see many of her pictures on her blog.

This week I had the opportunity to ask Amy about her challenging work and tireless dedication to these people…

WOMEN’S EYE: You made a huge leap to a new environment. What made you want to go to Africa?

WOMEN’S EYE: You made a huge leap to a new environment. What made you want to go to Africa?

AMY: I have been passionate about the issue of sexual violence most of my life. My undergraduate thesis focused on mechanisms behind perpetration of sexual violence.

While in Chicago, I went to a Vagina Monologues’ showing where the last piece was an account from a woman in Congo. At the end of the piece, the actress gave information about the Congo, and indicated that it was the place with the greatest need, in terms of sexual violence.

I immediately felt moved to come here, though I can’t really explain why beyond that. A cousin said she knew a priest from North Kivu, where most of the violence was occurring. I didn’t have the language or professional skills to get a job in Goma or Bukavu, but Father Charles was more than happy to help me get here and get settled.

“There’s no quick fix and feeling powerless when faced with such wonderful people who are going through so much pain, is the most frustrating aspect.”

EYE: The sexual violence where you are in eastern Congo has been described as “the worst in the world.” How do you deal with what must be an intense situation on a daily basis?

AMY: I guess writing my blog helps, because I feel like I can share my experiences, but more importantly, I can share the stories of what people are experiencing here. For me, the most intense and frustrating part is not being able to solve anybody’s problems. There’s no quick fix and feeling powerless when faced with such wonderful people who are going through so much pain, is the most frustrating aspect.

AMY: I guess writing my blog helps, because I feel like I can share my experiences, but more importantly, I can share the stories of what people are experiencing here. For me, the most intense and frustrating part is not being able to solve anybody’s problems. There’s no quick fix and feeling powerless when faced with such wonderful people who are going through so much pain, is the most frustrating aspect.

But really, just being around people here is immensely helpful. Even girls who have been raped several times, or by several soldiers, still laugh and smile and think I’m really awkward and funny looking, and tell me so.

EYE: Your blog describing living and working in Mulo near Bukavu is heart-wrenching and fascinating. Are you writing it to let readers know about the difficult conditions that women face?

EYE: Your blog describing living and working in Mulo near Bukavu is heart-wrenching and fascinating. Are you writing it to let readers know about the difficult conditions that women face?

AMY: That’s the sole purpose of the blog. I hope to show people abroad what life is like here for the Congolese people, but I think it’s hard to access stories that are as difficult as the ones here without having the urge to look away. I guess I’m trying to give my perspective as well. And it helps me too.

EYE: Recently United Nations officials said that about 500 women were raped in eastern Congo in July and August, a figure double the number previously reported. One victim was a seven-year-old girl. Was this common knowledge or surprising to people on the ground?

“There’s a lot of horror here, but also a lot of faith, kindness and community.”

AMY: That was more than common knowledge; in fact it was infuriating for many here, because the article made it sound as if there were ONLY 500 victims in eastern Congo in July and August, when in reality that number doesn’t even come close. From what I’ve heard those 500 victims were attacked in a few villages near Goma, within the span of a week, maybe two.

On the ground, where I live, at least, it was surprising for everyone I spoke with about it, simply because they grossly under-represented the problem. In terms of the content, seven-years-old is younger than I’ve personally spoken to, but then again I’ve heard people tell me about babies who were raped, and/or had their heads bashed in. There’s a lot of horror here, but also a lot of faith, kindness and community.

EYE: The level of violence against women in the Congo is unacceptable. Is enough being done to stop it?

EYE: The level of violence against women in the Congo is unacceptable. Is enough being done to stop it?

AMY: In no way, shape or form. There’s nothing here. In Goma and Bukavu, the two largest cities in the Kivus, there are many organizations working to provide support and protection for victims, but it doesn’t even scratch the surface. And most of the violence is in the rural areas, where there is essentially no support, partly because of the violence, but also because of funding and man power.

Recently, the current President Joseph Kabila Kabange, officially banned mineral mining in the Kivus, yet I live next to a small diamond mine and there are men out there right now. A lot of action can be taken officially, in the eyes of the media, but if there’s no follow through, then it simply makes the problem worse because people think things are getting better, when really it’s just hot air in a public figure’s mouth. People continue to suffer, and politicians are able to cover up their crimes for a little bit longer.

“They’re truly incredible people, fighters and teachers.”

EYE: You’re beginning to help survivors start small businesses. What do you hope to accomplish?

AMY: Right now, I just hope to learn. The most effective thing I personally do is teach children how to make funny faces at me. I hope to help in a larger way, but I’m trying to understand the problems, and the things that get in the way of effective and sustainable aide.

The organization I work with, COPERMA, and the Director, Maman Marie Nzoli, are redoubtable and the most valuable assets I have here are their advice and guidance. I sometimes will jump into things thinking I know what’s right, and they patiently explain cultural differences to me, or explain that soldiers will steal chickens, but not guinea pigs. I mostly stand in the background and try to learn from them. They’re truly incredible people, fighters and teachers.

The organization I work with, COPERMA, and the Director, Maman Marie Nzoli, are redoubtable and the most valuable assets I have here are their advice and guidance. I sometimes will jump into things thinking I know what’s right, and they patiently explain cultural differences to me, or explain that soldiers will steal chickens, but not guinea pigs. I mostly stand in the background and try to learn from them. They’re truly incredible people, fighters and teachers.

EYE: The idea of “rotational credit” is a fascinating one. Can you describe?

AMY: When women are raped here, they are often raped in their fields, which are their occupations. Families farm to support themselves. Thus, when a woman is sexually violated in her field, understandably it will be terrifying to return to the field, and most of the time the soldiers remain in the area and so they can’t safely keep working. Their means of living is stolen, in addition to the horror of rape.

While working with a group of women who were recently raped during a specific conflict between governmental soldiers and Ugandan rebel forces, I asked them how I might be able to help them in some small way, beyond giving some emergency food supplies. They indicated they wanted to sell different items on the side of the road, which is also a common occupation here.

I decided to allocate $30.00 for each woman, in the form of peanuts, dried fish, a sewing machine and palm oil, in order to help them start these businesses. Maman Marie explained rotational credit, something she had been doing with communities before the war started. A President of a group of around ten people starts out with a certain amount of money, in this case $30.00, in the form of a saleable item, such as peanuts.

They sell the item for a few months, and when they have made $32.00 back, plus enough to keep their business going, they give the $30.00 to the next woman in the group, and the President guards the $2.00 for emergency illness within the group.

The money keeps rotating, and when all of the women in the group have benefitted, they start the rotation again. In this way, we are able to help seventy women, rather than just seven.

“The Congo is a pot of gold with a hole in the bottom…you name it, the Congo has it, and several countries are exploiting it.”

EYE: You talk about the political leadership, that people have few opinions about it for fear of being killed. Your blog is brutally honest. Are enough people aware of the atrocities being committed against these women to turn the situation around?

AMY: If by “people” you mean people in high places, such as international leaders, then definitely. They’re not stupid, and they’re not gullible. But that doesn’t mean they’ll do anything about it. The Congo is a pot of gold with a hole in the bottom, and the international governments don’t want to patch it up while there is a river flowing from it. It’s not just gold either, it’s diamonds, coltan, rubber, oil, uranium even. You name it, the Congo has it, and several countries are exploiting it.

In terms of people in the general population, who do care and do want to help affect change, then no. While I was still in the United States, it was very difficult to get a feel for what was actually happening here and why. This is another reason I started the blog, to try and give a more focused and personal account of a problem that’s highly sensationalized and not easily accessible from far away.

In terms of people in the general population, who do care and do want to help affect change, then no. While I was still in the United States, it was very difficult to get a feel for what was actually happening here and why. This is another reason I started the blog, to try and give a more focused and personal account of a problem that’s highly sensationalized and not easily accessible from far away.

EYE: You describe journeying to try to help some women in need when a man that you didn’t know tried to kiss you in a hotel. How do women protect themselves in this threatening environment?

“It’s chaos in every direction; I truly don’t know how these incredible women wake up every day and keep fighting to survive.”

AMY: They don’t. The only thing they can really do is try to hide, be at home before dark. But soldiers enter the homes at night in Butembo and the villages all the time. I recently got word that a woman and her 14-year-old daughter were raped at the same time in the same room, and the father was killed in Butembo. That was just one story, and there was nothing anyone could really do. I didn’t even seek them out, because there’s nothing I can do for them.

It’s chaos in every direction; I truly don’t know how these incredible women wake up every day and keep fighting to survive. I can say I’m helping them, but in truth, despite being in the midst of such suffering and pain, they’re renewing my faith in the strength and spirit of humanity.

It’s chaos in every direction; I truly don’t know how these incredible women wake up every day and keep fighting to survive. I can say I’m helping them, but in truth, despite being in the midst of such suffering and pain, they’re renewing my faith in the strength and spirit of humanity.

EYE: What is the root cause of this level of sexual violence against women in the Congo? You ask this question on your blog.

AMY: It’s extremely complex, more complex than I ever could have imagined. Culture, gender roles, poverty, war, fear, insecurity, power, all come into play and don’t even scratch the surface. But the most significant contributor here is the war.

The chaos provided by the constant presence of violence and suffering, drastically increases the effects of all of the other mechanisms. The war is where we have to start, because it doesn’t just create an atmosphere where rape is almost accepted, it slowly destroys a culture and a people. Or at least, it’s trying to.

“…you start with security, food, shelter, and medical treatment. Then you try and work with sustainable development, as the soldiers trickle away.”

EYE: You’ve been told that it’s not safe to go near women who were raped by soldiers from a certain area. And yet you say you will help no matter what. How do you face this kind of danger?

AMY: The people I know here on the ground are much more knowledgeable about what’s actually going on, and I trust them with my life. If I want to go into an area where there are women in the bush who haven’t had medical treatment, Maman Marie will tell me yes or tell me no. And her word, for me, is final.

We can still find ways to help though. For example, in one of my blogs I mentioned a boy who was specifically targeted and raped several times by soldiers. He was hiding had been hiding in the bush for several days, with no real access to clean water, food, or medical treatment.

If you bring a car into an area where there is a confrontation, the soldiers will think you have money and will target you and rob you. If you bring a white person and a car, they’ll know you have money, rob you and then kill you.

Maman Marie told me we absolutely couldn’t go in to extract the boy, but we were able to send a COPERMA colleague on my motorcycle. He and the Chief of the village were able to bring the boy into Butembo where he received medical treatment with an organization called FEPSI, and even had a basic session with a counselor.

Maman Marie told me we absolutely couldn’t go in to extract the boy, but we were able to send a COPERMA colleague on my motorcycle. He and the Chief of the village were able to bring the boy into Butembo where he received medical treatment with an organization called FEPSI, and even had a basic session with a counselor.

There’s definitely a limit to what can be done, but in my opinion, you start with security, food, shelter, and medical treatment. Then you try and work with sustainable development, as the soldiers trickle away. Little by little, is how you help, I guess.

“The Congolese Aid workers I work with are incomprehensible to me… I can only hope to be able to work as tirelessly and with as much compassion as they do.”

EYE: How do AID workers deal with the overwhelming nature of the task?

AMY: The Congolese Aid workers I work with are incomprehensible to me. When I feel tired or overwhelmed, they just say, “the Congo is suffering” and keep working. They can’t afford even to have a beer or two as a break, and all of the money goes directly towards helping the women and kids. Once in a while I’ll buy everyone a drink and a meal, and it feels great to see them relax for a minute. I honestly don’t know how they do it.

I can only hope to be able to work as tirelessly and with as much compassion as they do. I’ve been doing this for 6 months; they’ve been doing it for 14 years, and have lived through a lot of the horrific things we’re trying to fight.

There’s a wall that has to be built, it feels funny having it there, sometimes I worry I’m losing my compassion, but really I think it’s just a necessary thing for anyone working with suffering of any kind; in the States, in the Congo, in Afghanistan, at home, wherever. If you sacrifice yourself, you can no longer help others.

EYE: You drive 7 hours through the dust to reach people. You ride 40 minutes up a mountain to get to your dark office to open up your computer. How do you keep going?

EYE: You drive 7 hours through the dust to reach people. You ride 40 minutes up a mountain to get to your dark office to open up your computer. How do you keep going?

AMY: I think you have to want to be doing it. A friend once asked me if I thought I “must” be here, and I said no, I “want” to be here. He said as soon as you start feeling like you must be here, then you’ll not only stop acting from compassion, but also lose that compassion in terms of taking care of yourself. Want vs. Must.

EYE: The stories that girls tell you about what they’ve experienced are horrendous….girls at 11 who see their parents killed and are raped by soldiers and civilians after. Is there international outrage?

AMY: Essentially, nothing; nothing palpable. There’s a lot of emotion, it’s an easily sensationalized topic, because it hurts to hear about. But beyond being hurt, nobody seems to be doing anything.

On a local level there’s a huge response. I talk to a lot of Congolese people fighting in their own ways, trying to start small Non-Governmental Organizations. Just this morning I had someone stop by who started an organization trying to help women who are forced to prostitute themselves in Butembo because of the extreme levels of poverty.

On a local level there’s a huge response. I talk to a lot of Congolese people fighting in their own ways, trying to start small Non-Governmental Organizations. Just this morning I had someone stop by who started an organization trying to help women who are forced to prostitute themselves in Butembo because of the extreme levels of poverty.

On an international level, it’s so small I personally can’t see it; at least, not in the region where I am working. On a governmental level, it’s not just non-existent, it’s in the negatives, considering the governmental forces are one of the main groups raping women.

“They are constantly in fear for their lives, their bodies, their children, yet they find ways to be kind and friendly…”

EYE: Please describe the spirit of these women.

AMY: I have never in my entire life understood the strength of humanity as much, and more specifically, the strength of women, as I do here. Of course, these girls are affected deeply, simply because they’re able to show their spirit doesn’t mean it’s easy.

They are constantly in fear for their lives, their bodies, their children, yet they find ways to be kind and friendly and interactive with a world that has truly deemed them unworthy. They, more than anything, give me hope that this country will be able to recover.

EYE: Some of the children are a product of rape. How are they coping? You took a photo of a soulful little boy with his dragonfly eyes.

EYE: Some of the children are a product of rape. How are they coping? You took a photo of a soulful little boy with his dragonfly eyes.

AMY: The children I’ve met are too young for me to have an idea of how they’re coping. They’re normal children, eager for attention, shy when they have it, interested in having their image captured in a little black box.

Through the children, however, is another way in which these women and girls show their strength. Though many of them express that raising their children, who are products of rape, is difficult and often extremely distressing, I’ve never seen them treat their children with anything less than the utmost motherly love.

When I ask what the women and girls hope for in life, almost always they say they hope for a life without suffering, and maybe even with an education, for their children.

When I ask what the women and girls hope for in life, almost always they say they hope for a life without suffering, and maybe even with an education, for their children.

EYE: How long will you stay?

AMY: If I don’t end up going to Graduate School next year, I may be here indefinitely. It’s all rather up in the air right now, but no matter what, I want to be here.

EYE: When do you think there will be peace?

AMY: That’s impossible to answer. I think that could be in a couple of years or never. It depends on when the leaders of all international countries, especially in the Western world, as well as the Congolese government, start holding themselves responsible for the horrifying things happening to the people here; people who somehow maintain hope and a little laughter, even when the rest of the world seems to have left them to suffer inexplicably, at the hands of men who have the gall to call themselves soldiers.

“…speak about it, do some research, and find a way to help that fits with your interests and passion.”

EYE: What’s the biggest lesson you’ve learned? How can people help?

AMY: People need to at least explore what’s really going on, and use their voices. That’s the best way: speak about it, do some research, and find a way to help that fits with your interests and passion. There are so many levels that right now are lacking desperately; from a grassroots level up to lobbying for change in international governments.

There was recently a bill passed by the House and the Senate, called S.891 Congo Minerals Act (Senate) and the House Bill 4128. It didn’t get much coverage in the press and almost definitely won’t be enforced. People can voice their support of that or boycott companies based on whether or not they prove that their minerals aren’t conflict minerals.

If you go to enoughproject.org, you can find more information about the problem of minerals. Getting conflict mineral flow under control is a huge step, but there will still be a lot more to do.

And, of course, people can always donate to COPERMA, the organization I work with, through the Crosier Catholic Priests I live with. I’m working to help them start a website, but it’s just getting started, so right now we’re working through the kindness of the Crosiers. All money is sent directly to Maman Marie Nzoli, and I can guarantee, is used to help the victims of the war on the ground.

EYE: Thanks so much for your time, Amy.

QUESTION: Do you ask yourself how you can help these Congolese people in great need?

Leave a Reply