By Patricia Caso/May 25, 2014

Twitter: @carlottagall

For twenty years British journalist Carlotta Gall covered the volatile conflicts in Chechnya, Kosovo, Serbia and other war–torn countries. She spent the last dozen years reporting from Afghanistan and Pakistan, winning a Pulitzer Prize for her work at the New York Times in 2009.

“All reporting should be about the humanity. I did learn early on that wars are all about the people. They are not about the generals ordering in the tanks.” Carlotta Gall

Carlotta takes on a controversial subject in her latest book, The Wrong Enemy: America in Afghanistan 2001-2014, where she questions whether Afghanistan should have been the target for war. I was fascinated and excited to speak with Carlotta about her dedication toward her profession. She has a passion for getting the story right from the front lines while facing tremendous danger …

EYE: The New York Times called your book a “searing expose of Pakistan’s involvement in the Afghan War.” You wrote that “Pakistan, not Afghanistan, has been the true enemy.” How did you come to that conclusion?

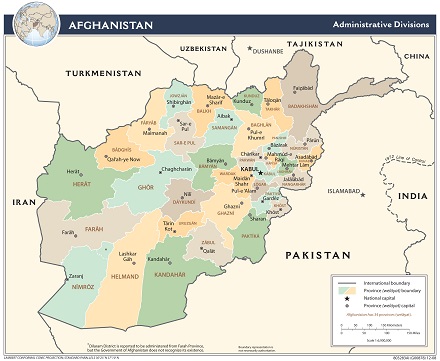

CARLOTTA: When other reporters went off to Iraq, I stayed in Afghanistan. In 2002-2005, I traveled freely and spoke to so many people that it became clear to me that Pakistan had not stopped in its support for the Taliban.

CARLOTTA: When other reporters went off to Iraq, I stayed in Afghanistan. In 2002-2005, I traveled freely and spoke to so many people that it became clear to me that Pakistan had not stopped in its support for the Taliban.

By 2006, I remember becoming very alarmed at the scale of their venture. It was suddenly incredibly dangerous for all of us and for the NATO troops coming in.

It looked like half the country, the south, would be back in the hands of the Taliban. That’s when I realized that Pakistan’s aim was far grander than I had originally thought.

EYE: You say you were aware that bin Laden was a threat before 9/11. You write that “according to one inside source, the Pakistani Intelligence (ISI) actually ran a special desk assigned to handle the al Qaeda leader.” What led you to those discoveries?

CARLOTTA: I knew bin Laden was in Afghanistan and doing great damage there well before the September 2001 attacks. I was reporting from the Balkans for The New York Times on 9/11. When I saw the plane go into the second tower I said, “That’s bin Laden.”

I actually knew enough at the time of what was going on. I knew he was trouble. I’d been in Chechnya where the same group of Arabs had been coming in and causing radicalism and trouble. So I was better versed than many journalists.

I knew the connection with Pakistan, but knowing that bin Laden was the mastermind mainly resulted from reporting from the ground for so long. And, that kind of reporting made the difference in connecting the dots to uncovering Pakistan’s aid to bin Laden.

EYE: What do you want readers to take away from The Wrong Enemy?

CARLOTTA: I really wanted to tell the whole tale of the Afghan War so that people who come later, especially younger people who might not have been alive during 9/11 or during the war, can understand from start to finish what happened. I feel I offer something important which was witnessing everything–being there.

PBS Newshour: Author Carlotta Gall on What Went Wrong with U.S.-Afghan Relations

Also, I want readers to understand some of the motivations of the Afghans, especially people like President Hamid Karzai, who I think is now getting a very hard time. Of course he is not perfect. What leader is flawless? I felt I needed to give the Afghans a voice.

EYE: What is the hardest reality for the Afghan people now?

CARLOTTA: It ‘s been a long hard slog for everyone concerned in the intervention there. But, when the troops leave, the aid will be cut, the embassies will diminish their staffs and the financial assistance to Afghanistan’s budget diminishes. It is such an incredibly poor country, which cannot support itself.

If all that declines, they will be prey to both Pakistan and Iran, their neighbors who are very predatory. The whole effort of these last 12 years will be lost, and that shouldn’t happen.

There have been advances for women, education and even the inspiration for a better life. They worked hard for it because they believed they could achieve it.

They are half-way there. So it worries me that the West could easily just turn away again. I believe that would be catastrophic.

EYE: You are certainly no stranger to war reporting. You posted reports and wrote books on the Chechnya war in the late 1990s. How well prepared were you for the type of personal physical violence you’ve encountered on assignment? You’ve been betrayed, harassed, assaulted, and even punched!

EYE: You are certainly no stranger to war reporting. You posted reports and wrote books on the Chechnya war in the late 1990s. How well prepared were you for the type of personal physical violence you’ve encountered on assignment? You’ve been betrayed, harassed, assaulted, and even punched!

CARLOTTA: When Pakistani intelligence agents broke into my room in Pakistan, and the guy punched me wanting my handbag; I kind of resisted, which you are not supposed to do. He slammed his fist into my face.

I absolutely didn’t see it coming. I went down straightaway, right down on the coffee cups and everything. I was not prepared. It was not one of my better moments. So I’m not well-prepared. I’ve never taken a self-defense course.

When it comes to actual war reporting, most of us get hardship courses, where you get all the basics on how to look after yourself in a war zone. When I took the course, I’d already been covering Chechnya for several years.

So much of it you learn as you go along and is common sense. You also pick up great advice from more seasoned journalists whom you meet along the way.

EYE: What went through your mind when you heard about journalist Kathy Gannon’s wounding and photographer, Anja Niedringhaus’ death in Afghanistan?

CARLOTTA: It was heartbreaking, really. Those were two people who really knew what to do and how to handle themselves in a war. It could have been me. Any one of us could have been going to an outlying province to witness the elections and expose any problems or difficulties. I said, “Oh, my God, how could it have happened to them?”

“When you are out there, you drop all competition; you look out for each other and work together. It was dreadful news to get. Thank goodness Kathy is on the mend. But, it’s a great loss to lose Anja, who was so talented and so hardworking.”

EYE: Where do you get your nerves of steel?

CARLOTTA: I think I’m quite a calm person, which has a lot to do with low blood pressure and just being pretty slow in the morning. It’s actually the profession of following the story, getting your teeth into it and wanting to find out what happened that keeps you going. You’re so busy with all that.

One of the greatest concerns is for the safety of the people who work with me like local reporters, translators, drivers, fixers, etc. They remain after you fly out. So you are so often thinking about how to protect them, how to avoid giving away sources, etc. It’s all involved in the reporting.

Photo: Robert Nickelsberg, Getty Images

EYE: How did you decide on a career as a war correspondent?

CARLOTTA: I didn’t. It just happened. I was increasingly drawn to current affairs and politics. When I did join my first newspaper, the Moscow Times, I was fascinated when the war started in Chechnya and I asked to go.

It was really when I got there and found I could manage on the ground and get the story filed, which was incredibly difficult in Russia in those days. You had to run around looking for a telephone exchange and dictate on the line. When I found I could do it, they kept sending me.

“I think in the end I just felt that if people are dying or governments are prepared to kill their own citizens to achieve aims, that is one of the most wrong things in the world. You had to write about it, expose that and show what was happening.”

EYE: How would a young person start in a war reporting career?

CARLOTTA: Go to a foreign country, preferably one where you speak the language so you don’t have problems with translation. Work for a local newspaper. I went to work for the Moscow Times speaking Russian. Everything was opening up from the Soviet Union in the Yeltsin years. We were all young graduates who all spoke Russian, so we worked with Russian journalists as well.

We were all running around all over the place, just getting these amazing stories. Since it was a national newspaper, you were straight in writing about Yeltsin going to war in Chechnya on the front page. That was incredibly exciting as well as a baptism by fire.

With Twitter, online websites and blogs, today’s youth have even more possibilities. I think in the end the tenets of good journalism are the same. Get the story and get it right.

EYE: What is the best advice you received?

CARLOTTA: I usually keep this secret. But, because of what happened to Kathy and Anja, it is fresh in my mind. A Chechnyan commander, who got it from his grandfather, who escaped Stalin’s purges, once told me: “Never tell anyone where you are going or where you’ve come from.”

It was really advice to escape kidnapping of foreigners, but also to evade enemies in war. So far I’ve survived and use it today.

EYE: What have you learned about yourself as a war reporter?

CARLOTTA: People say war correspondents are old hacks and are very cynical. I found you get more vulnerable to your feelings as you go along. Each case of human suffering you see just reminds you of the other ones. It can build up until it’s almost overwhelming.

EYE: How do you deal with that?

CARLOTTA: You just have to take a break, stop that type of reporting, turn to something else, go on holiday or just do some editing instead of war reporting. You have to pace yourself. Or read.

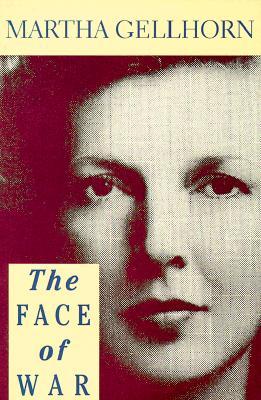

I always keep one of Martha Gellhorn’s books close at hand. I love the lightness and almost conversational style she has of writing.

I always keep one of Martha Gellhorn’s books close at hand. I love the lightness and almost conversational style she has of writing.

EYE: What is key for you as a reporter?

CARLOTTA: The most important thing is being there, bearing witness, reporting it as it is. I am not a columnist or a great theorist. I’m really a basic daily reporter. When I put it together in a book, I try to give it more sense. As you can see, the book is still full of the basic reporting of “I was there. This is what I saw. This is real. That’s how it was.”

All reporting should be about the humanity. I did learn early on that wars are all about the people. They are not about the generals ordering in the tanks. They are about what the tanks crushed in their way as they went forward.

The war is what you see happening on the ground, which is incredibly important to report, so that people back home, leaders, families back home know what’s happening. There’s a great thirst to know what it’s like. I see that in readers’ reactions to my stories. I know it’s a very important job we are doing.

EYE: Thank you, Carlotta. Your courageous, insightful writing is an inspiration for readers and aspiring reporters alike. Continued success as you embark on your latest assignment in Tunisia as the New York Times’ North African Bureau Chief.

###

Leave a Reply