By Laurie McAndish King/April 8, 2015

Photos Courtesy Lynsey Addario (@lynseyaddario)

“I was now a photojournalist willing to die for stories that had the potential to educate people. I wanted to make people think, to open their minds, to give them a full picture of what was happening…” Lynsey Addario

Lynsey Addario asserts, “I don’t think of myself as a war photographer.” Yet war photography is what she’s known for. It’s what earned her a Pulitzer Prize for international reporting and a MacArthur Fellowship or “Genius Grant.”

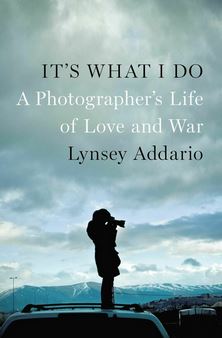

It’s what got her embedded in Afghanistan and landed her in a Libyan prison–blindfolded, bound, and beaten. And it’s the subject of her new memoir, It’s What I Do: A Photographer’s Life of Love and War (@penguinpress).

I met this extraordinary woman in a crowded auditorium at the San Francisco Jewish Community Center, where she spoke about situations I can barely imagine, and showed photos that were beautifully composed, yet horrifying.

Addario explained that she photographs conflicts not just for the sake of covering war, but because there are humanitarian and human rights issues she wants to expose. She has photographed victims of drought, famine, land mines, mental illness, AIDS, genocide, and rape. Her documentation of bodies strewn across the desert in Darfur made it impossible for the government there to continue denying a massacre.

Addario explained that she photographs conflicts not just for the sake of covering war, but because there are humanitarian and human rights issues she wants to expose. She has photographed victims of drought, famine, land mines, mental illness, AIDS, genocide, and rape. Her documentation of bodies strewn across the desert in Darfur made it impossible for the government there to continue denying a massacre.

She has also shot night raids and refugees, soldiers receiving incoming mortar rounds and children playing outdoors in war-torn Benghazi. Cars burning, bombs exploding, a dying soldier’s last moments–these are the images that first drew me to Addario’s work.

Her memoir tells the story of Addario’s life as a conflict photographer, a single woman, a wife, a captive, a reluctantly pregnant freelancer in a man’s profession, and a mother. It is filled with images from Pakistan, Afghanistan, Sudan, Iraq, and Libya.

Addario’s style is gritty. Some of her photos show billows of the dark smoke that rises after bombs fall. Many use a dramatic lower-left-to-upper-right diagonal composition to help convey the scene’s tension. Some show bleeding soldiers, corpses, or skeletons.

Others were taken at night, without enough light for a good exposure. One was taken through green night-vision goggles, and another glows with the red light that was used to avoid enemy detection. They all show human lives in intimate detail.

What prepares a person for this kind of career? Were Addario’s parents journalists, or military personnel, or doctors? No–they were both hairdressers. Their home in Westport, Connecticut in the 1970s was “a kaleidoscope of transvestites and Village People look-alikes.” Everyone was welcome at our house, Addario says. The doors were always open.

When Lynsey was thirteen her father gave her a Nikon FG, her first camera. She was hooked. Too shy to shoot people, Lynsey began by photographing architecture and flowers. She eventually got work as a stringer with the Associated Press, and graduated to covering protests, press conferences, and accidents. She shot one of Monica Lewinsky’s earliest public appearances, on the TODAY Show.

Addario on the advantage of being a woman photographer

Addario’s first serious assignment as a photojournalist was for a story about the working conditions of transgender prostitutes in New York in 1999. Her mentor at the Associated Press (whom she refers to as “Bebeto”) figured Lynsey was perfect for the project, given her family’s lifestyle.

Getting the photos involved spending weeks with her subjects–without a camera–in order to gain their trust, and then five months more getting the shots.

“I had no idea that I would become a conflict photographer,” Addario says. “I wanted to travel, to learn about the world beyond the United States.”

A year later, at twenty-six, Lynsey found herself in Afghanistan, there to photograph the lives of women living under the Taliban. It was illegal to photograph any living thing in Afghanistan at that time, but she had access to women in a way men did not. Lynsey literally knocked on doors, spoke with women, and asked to photograph them.

I was not surprised to learn that Lynsey always got her photos. From her presence onstage where she spoke, it was clear that the journalist was both outgoing and determined. But beyond that, she didn’t look like a war photographer. Wearing a fitted black v-neck blouse, skin-tight dark jeans, and black booties with high heels, Addario looked more like a model.

Tabitha Soren, a Berkeley photographer and former news correspondent for MTV and NBC, interviewed Lynsey onstage at the JCC after the photo-slideshow and talk. Addario, of Italian descent, spoke eloquently with both her words and her hands.

“The more I worked, the more I achieved, the more I wanted,” she explained. “I think I’m pretty tortured about my work as a photographer. I’m always thinking about composition, light, access. I never feel like I’m doing enough as a journalist, as a photographer.”

Conflict photography is difficult for many reasons, and combat is one of the worst. “I’m not gonna start crying when the bullets start flying, ” she said. Addario trained hard before embedding in Afghanistan. She needed to be able to keep up under extremely rigorous conditions of high altitude, traveling on foot in mountainous terrain, and carrying her tent and enough food and supplies for a week–as well as being shot at.

The last thing she wanted was to be with soldiers who thought, “Oh God, the chicks are here.”

In January, 2003, Addario was on assignment in South Korea, and the U.S. was clearly gearing up for war in Iraq. Lynsey knew she would go to Iraq and that she would need body armor there so she ordered it herself, online. From South Korea. It wasn’t easy.

As Soren read a passage from It’s What I Do describing the process, Lynsey sat onstage with her legs crossed and twined together, her hands clasped tightly on her lap, fingers laced together. She was uncomfortable hearing the passage, even though it evoked a big laugh from the audience.

“Basically, I have no idea what I am looking at–ballistic, six-point adjustable tactical armor, etc. Please understand that this language is not familiar to me–I grew up in Connecticut, was raised by hairdressers.”

The following year, with government permission, Addario took photos of injured American soldiers in Fallujah. Her editor at Life declined to run the story, saying the images made “too strong a story for the American public to see.” Addario tells us about her reaction:

“… something in me had changed after those months in Iraq. I was now a photojournalist willing to die for stories that had the potential to educate people. I wanted to make people think, to open their minds, to give them a full picture of what was happening … When I risked my life to ultimately be censored by someone sitting in a cushy office in New York, who was deciding on behalf of regular Americans what was too harsh for their eyes, depriving them of the right to see where their own children were fighting, I was furious … Every time I returned home, I felt more strongly about the need to continue going back.”

Addario on photographing injured soldiers in Fallujah/11-2004

Addario did keep going back. In the first three months of 2011, she worked in South Sudan (shooting a Newsweek cover with George Clooney), Iraq, Afghanistan, Bahrain, and Libya–where she was kidnapped and beaten.

The first three days were violent, she said, as “we were shifted along the front line. Each new captor asserted his power, beat us, told us they would kill us.” One caressed her while she was bound and blindfolded, repeating over and over, “You will die tonight.”

Several days later, when she was living off the front line in an apartment under house arrest, one of her male captors offered to buy some supplies. What did she want? “Coffee. Cream. Sugar. Shampoo. A toothbrush,” Addario listed her priorities. Did she need “any feminine things?” he asked delicately, in a surprising show of empathy.

The man returned with “twenty-five bags of groceries. Enough food for a year! We’re never going to be released,” Addario despaired. He also brought new Adidas tracksuits for the three male captives who were her colleagues. Addario, the only woman, got special supplies: an extra-large tan velour sweatsuit embroidered with teddy bears and emblazoned with the words The Magic Girl! plus three pairs of underwear decorated with the words Shake it Up!

Lynsey Addario was released a few days later. As she settled back into her life, the inevitable question arose: Would Lynsey cover another war? Of course!

She did pause, if only briefly, to have a child. The criticisms she received for traveling while pregnant, risking assault and disease, possibly putting her life and that of her unborn child in jeopardy–did not deter Addario. What she does is a calling, which she will not–she cannot–give up. Like all professional women, Addario struggles to balance her career and personal life.

“I was more selective about assignments after the birth of my son,” she writes, “and I weighed the importance of every story with the importance of every day that would keep me away from my family.”

Motherhood has added an unexpected depth to her work, though. She feels “happier and more complete with my new family than ever before,” but she also suffers more.” Being away from Lucas was worse than any heartbreak, any distance from a lover–anything I had ever known.”

The indescribable love Lynsey feels for her son amplifies the atrocities she sees on assignment. Now she can imagine the depth of grief a parent feels when she loses a child to war or disease or starvation.

She is still photographing conflict around the world, opening our eyes to horrific situations most of us will never see in person. She still has the Magic Girl! sweatshirt. And she’s still shaking things up, doing work that makes a difference.

You’ll be hearing lots more about Addario and her work–Steven Spielberg is set to direct a film based on It’s What I Do, with Oscar-winning actress Jennifer Lawrence portraying Lynsey. In the meantime you can see her talk at the San Francisco Jewish Community Center below.

Facebook page for Lynsey Addario

You can find the ebook edition: itswhatidobook.com

Leave a Reply