By Laurie McAndish King (@LaurieKing)/January 12, 2016

TWITTER for Jessica and Kennedy: @hope2shine

Jessica Posner grew up a middle-class American in Denver. She hadn’t seen much of the world, and when she had an opportunity to study overseas she chose to do political theater work in Kenya. Jessica ended up living in a slum with no streets, no toilets, no running water, no electricity and no public services. Then she got malaria.

“No one believed Jessica could survive,” Kennedy Odede, her husband, says. “Every morning my friends knocked on my door and asked: Is she dead, or is she alive?”

Jessica Posner and Kennedy Odede’s lives are linked by one unlikely circumstance after another. They met when Jessica was taking a junior year abroad and Kennedy was organizing street theater to raise awareness about sexual violence in his community. Kennedy lived in a Nairobi slum called Kibera, a warren of hopelessness the size of Central Park.

Jessica Posner and Kennedy Odede’s lives are linked by one unlikely circumstance after another. They met when Jessica was taking a junior year abroad and Kennedy was organizing street theater to raise awareness about sexual violence in his community. Kennedy lived in a Nairobi slum called Kibera, a warren of hopelessness the size of Central Park.

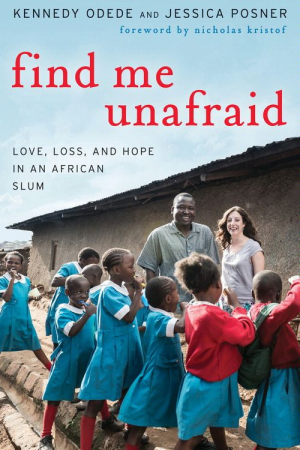

Jessica and Kennedy were in America together, celebrating the launch of the book they co-wrote, Find Me Unafraid – Love, Loss, and Hope in an African Slum. A friend had told me about their remarkable story, so I was excited to hear the couple speak at Book Passage in Corte Madera, California.

It’s hard to imagine two people more different on the surface. Jessica wears a stylish dress; her animal-print pumps have three-inch spike heels. Reserved on stage, she lets Kennedy do most of the talking.

Kennedy speaks with animation and charisma. Until a few years ago he’d had so little exposure to Western culture that he was astonished by the abundance of a school cafeteria and the luxury of hot running water.

Jessica and Kennedy tell us about the work they have done together, which sounds like a minor miracle: setting up and running a free school for girls in the slum, making clean water and medical care accessible and helping dozens of individuals start small businesses.

It hasn’t been easy. Kennedy grew up in extreme poverty, taking to the streets and using drugs when he was just 10 years old to help alleviate the pain of his situation.

“I had a job in a factory where I earned $1 for 10 hours,” Kennedy says. “I saw people getting old in their jobs. My best friend was shot and killed by the police; my sister was abused. I was sad and angry and hopeless.”

But Kennedy Odede was also resourceful, resilient and determined. He read A Testament of Hope: the Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr., and was inspired to build a better future.

“Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate. Only love can do that,” he read in King’s book. “Faith is taking the first step, even when you can’t see the whole staircase.”

Kennedy realized that the people of Kibera needed to solve their own problems, and he was determined to do just that.

“Where are the donors? Where is the money?” his friends asked. “You are crazy!”

“This is not a non-profit,” Kennedy responded. “This is a movement. We do not need donors to clean our streets. We do not need donors talk about issues that affect us.”

Odede was off to a strong start. He bought a twenty-cent soccer ball and started a team to give people something constructive to do. He organized neighborhood clean-ups and street theater. He raised awareness about sexual violence.

He co-founded a youth group called Shining Hope for Communities (SHOFCO) and got his fellow citizens talking about how to improve their living conditions. “I got elected mayor of Kibera,” Kennedy says, sounding a little surprised.

Then Jessica turned up. She moved into Odede’s cramped home, reasoning that it would be hypocritical to live in comfort outside the slum while she was working with the people of Kibera. The two strategized, and decided that if they could change the realities for women and children, everything else would follow. They would open a free school for girls, starting with the youngest, the brightest and the most vulnerable children.

Jessica knew how to apply for grants in America. She had friends whose families donated money. She raised $10,000 to start, and Kennedy worked with community members to arrange a small space for the school.

It had to be free in order to reach the girls most in need, but the school wasn’t set up as a charity. The students’ parents contribute their time – five work-weeks each year – in exchange for the girls’ education. Some of the students are orphans, so friends or relatives donate time for them. Brothers, sisters, cousins and neighbors all work together to help the school and build community.

Jessica and Kennedy hired the best teachers in Kenya, and after just a year their students were speaking good English. Opportunities were opening up, and the community began to understand the value of educating girls.

Eunice Akoth’s Dream: A poem from a 5th grade student at the Kibera School for Girls

The Kibera School for Girls is adding one grade each year; eventually it will go through 8th grade. After that, the school will try to arrange admissions to high schools, boarding schools and even college for all its graduates.

The school made even more sense when Jessica and Kennedy added a health clinic and a source of clean water. TWE first interviewed Jessica in 2010, when the clinic had just opened. Services now include primary preventive care, women’s and children’s services, HIV care and a child nutrition program.

By including holistic services so all members of the community benefitted directly, they made the school into a portal for large-scale social change.

New York Times Op-Ed Columnist Nicholas Kristof, who writes about human rights, women’s rights and global affairs, has helped publicize Jessica and Kennedy’s work. Now even the government wants to help. (“They want our votes,” Kennedy clarifies.)

And since they have demonstrated what is possible, Jessica and Kennedy are getting requests from young people across Kenya – and around the world – to replicate SHOFCO and the school for girls. “Young people look at me,” Kennedy says, “and see that it is possible to change. We can do it. We don’t have to wait for the government, or for big donors.”

“Standard international development is very top-down,” Jessica explains. “But this is bottom-up. Most of the funding comes from individuals. It only takes $100/month to sponsor one girl, and give her two meals a day.”

Although things are getting better, many residents of Kibera still struggle every day. The political situation has improved significantly since 2007, when Jessica and Kennedy began working together. Kenya’s government is much stronger now, but there is still no functional government in the slum, and no police protection. Poor women still have a dismal life.

But SHOFCO isn’t waiting around for donations. They provide computer, adult literacy and business skills classes for Kibera residents. SHOFCO’s sanitation efforts include cutting edge bio-latrines, community toilets and hygiene and sanitation education initiatives.

All this has grown from Kennedy’s initial work to create a safe, productive space for community members to gather and improve their lives. The real magic of Jessica and Kennedy’s collaboration is the local participation Kennedy inspires, combined with the outside funding prowess Jessica provides.

This approach works so well because it empowers the people of Kibera and lets them decide for themselves how best to use outside aid. Most of all, it engenders hope by demonstrating that a better life is possible.

Jessica and Kennedy took their collaboration beyond SHOFCO – they were married in June of 2012, and they will undoubtedly keep right on making things happen. As a friend said at their wedding, “It’s never going to be dull!” I have a feeling there are more miracles on the horizon.

###

Leave a Reply