By Patricia Caso/February 2, 2016

TWITTER: @rachelswaby

Other than Rachel Carson, Marie Curie, Jane Goodall or Florence Nightingale, I learned very little about historical women who made incredible scientific advances during my grade school and high school years. For instance, who knew it wasn’t all about acting for Hedy Lamarr? Turns out she was an inventor of a communication system that is now the basis for wi-fi, bluetooth and the GPS!

“I thought it would be great to have more and better profiles of women in science and not rely on obituaries for information.” Rachel Swaby

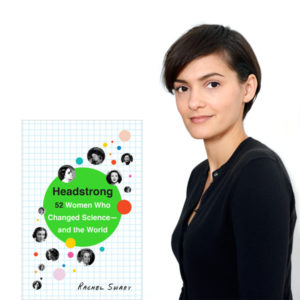

Based on Rachel Swaby‘s terrific book, Headstrong (Broadway Books), it seems that generations have missed learning about exciting scientific achievements from women around the world.

I had a chance to catch up with a very busy Rachel Swaby and find out more about the uncredited global heroines that she has chronicled in Headstrong.,,

EYE: How did you decide that finding historical women in science would be important and make a great book?

RACHEL: In 2013, I read an obituary in the New York Times for the rocket scientist Yvonne Brill. I never heard of her. I’m paraphrasing now. Her son described her in this way: “She made a mean beef stroganoff, followed her husband from town to town and was the world’s best mom.” It wasn’t until the second paragraph that the obituary noted she was also a brilliant rocket scientist.

Rachel on Face the Nation/CBS, Published 9/6/15

This sole American woman working in rocket science in the 1940s designed a propulsion system that keeps satellites in orbit, and yet the first thing written about her was her cooking and being a mom.

Like a lot of other people I was upset about that obituary and that was the start. I thought it would be great to have more and better profiles of women in science and not rely on obituaries for information.

EYE: How did you arrive at the title Headstrong?

RACHEL: I really liked “headstrong” as two separate words, the power of smart.

EYE: Who of your 52 profiles most typifies the characteristic of headstrong?

RACHEL: They are all headstrong. Rita Levi-Montalcini, a Nobel Prize winner from Italy, was a doctor. During World War II she was told she could no longer practice medicine because she was Jewish. Instead of packing it in, she set up a secret bedroom lab and rode her bike to her neighbor to get fertilized chicken eggs to do her experiments.

She was very creative in using what she had around her to make her lab, even filing down knitting needles so she could have scalpels. I love how she found a space for herself in extraordinarily hard times.

EYE: You wrote about an American, Alice Hamilton, who didn’t let much stand in her way.

RACHEL: She doesn’t conform to what we would think is scientific lab work. Looking into a cause of a typhoid outbreak in her neighborhood, Alice went into the housing of people infected, interviewed them, took mosquitoes, and observed conditions.

She used that same method to report on occupational disease. We didn’t know which factories manufactured with lead so she would go into the factories, interview people and observe the conditions.

When managers got smart to what she was doing and blocked her access, she would go into hospitals, pull hospital records and interview people at home where she thought they would be more comfortable talking about work.

She became the foremost expert in occupational disease in the U.S. At a time when Harvard did not admit women or hire women, she was hired for her work on occupational diseases.

As a journalist I really admired that she walked into all these places because I think her work was definitely better for it.

2015 National Book Festival/Library of Congress/Published 12/11/15

EYE: Was there any research that really surprised you?

RACHEL: I think the range of the mathematicians and scientists was much wider than I expected. I didn’t know most of the women in the book, and I thought I would since I love writing and reading about scientists.

At one point, I was searching through books and articles in the geology area and I found Inge Lehmann, who discovered the inner core of the earth! It was so surprising to me because like every kid, I learned about the earth’s layers in geology class.

How on earth did I not know that it was a woman who made the discovery? I know I would have remembered that. It would have stuck in my brain. It was something so obvious that we could have learned as kids and didn’t.

EYE: Did you find any interesting patterns with the women you profiled?

RACHEL: What I found refreshing was that everyone was so different. There wasn’t a certain type of person that was able to be a mathematician or scientist. Certainly some common threads were perseverance, grit and real creativity.

I think big discoveries happen when you think outside what is expected.

Also, in reference to the fact that all my profiles died one hundred years ago, it was a lot harder to get a science education as a woman than now. Many women weren’t able to have office space in a university; they were told they weren’t allowed to practice.

Rita Levi-Montalcini set up a secret bedroom lab; Rosalyn Yalow used a janitor’s closet for a lab so she could work on radiation detection. There has been some very amazing pioneering work done in some very strange places.

EYE: What can today’s aspiring scientists learn from your headstrong women?

RACHEL: There are so many ways to be scientists. Ruth Patrick, who died at 103, studied fresh water for its origins and water’s health. She was wading into rivers and exploring in her 90s.

Mary Anning was 10 or 11 when she found her first dinosaur because she was curious. She followed that curiosity for the rest of her life, not in a lab but out in the field.

EYE: Were there any inspirational revelations for you?

RACHEL: I didn’t think I had the brain for math and focused on English instead. Sophie Kowalevski, a Russian mathematician, said basically that it is the uniformed that confuses math with arithmetic. Arithmetic is a giant pile of binary numbers, just adding and subtracting.

But mathematics is more like poetry. For me, as an English major, that really struck a chord. She approached mathematics with such creativity and imagination. When you are going through the beginnings of mathematics, that sense of wonder and excitement, which are a set of tools that you can do incredible things with, is not always that clear.

EYE: What do you think is holding women back in science?

RACHEL: I think the structure of the scientific system can often be compared to an old boys’ club. Also, one big thing is role models. When I grew up there were pictures of Einstein on the wall but we didn’t have any pictures of any women working in science.

In other instances, if women want to get credit, they are encouraged to put a man on their team.

EYE: Has your perspective on women’s role in science changed in any way as a result of writing this book?

RACHEL: The math thing changed for me. I feel great regret about not understanding what mathematics might have been for me. It made me reexamine my own trajectory. I used to love science and remember the moment in a high school physics class when I thought maybe it wasn’t for me.

I was getting good grades and really interested in it, and, at some point, it just turned off. I think it’s kind of a shame. I hope now and in the future we can prevent that happening in a lot of young women.

The good news is the burgeoning interest in coding and more current role models like astronaut Sally Ride, but we still have a long way to go.

EYE: You are a freelance writer and have written many articles over the years for Wired. Why choose writing for your profession?

RACHEL: I loved writing at a very young age. I knew I wanted to be a writer. My mom was a really big reader. That really made a difference and was helpful. I just had to decide what kind of writing I wanted to do. I love telling true stories. I couldn’t make it up!

EYE: What is your advice for young women writers or scientists?

RACHEL: Start writing! Practice. Practice. Practice. With science, you can go out and start experimenting. There are many ways to get into it. Keep up the enthusiasm. Follow your interests.

EYE: Would you consider yourself headstrong?

RACHEL: Yes. I think I am… in a quiet way.

EYE: Well, Rachel, I think in your quiet way you have made a big impact in supporting young women’s curiosity and interest in science and writing. Thank you for your time and insights!

###

Terrific article; thanks for covering this important topic!

So glad you got to read this story. We love Rachel’s book and hope that the word spreads about it.