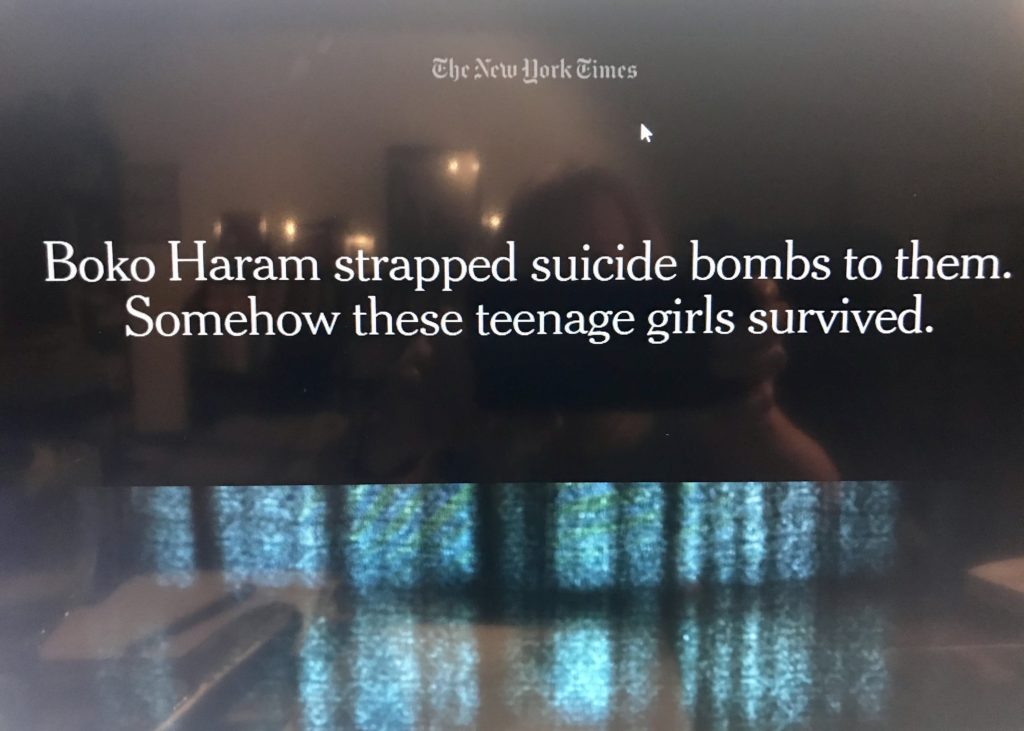

Dionne Searcey, the award winning New York Times journalist, wrote the unforgettable New York Times article in 2017 about Boko Haram girls who were trained to be suicide bombers.

“I saw women who had been strapped with suicide bombs who refused to carry out terrorists’ orders in northeastern Nigeria…These women were young and powerless and refused to kill anyone. It was really shocking that they had the bravery to fight one of the most dangerous terrorist groups in the world.” — Dionne Searcey

She now has a memoir, In Pursuit of Disobedient Women (Penguin Random House, 2020), which includes that story and is just one example of a behind-the-scenes look at what being a correspondent in a foreign country is truly like.

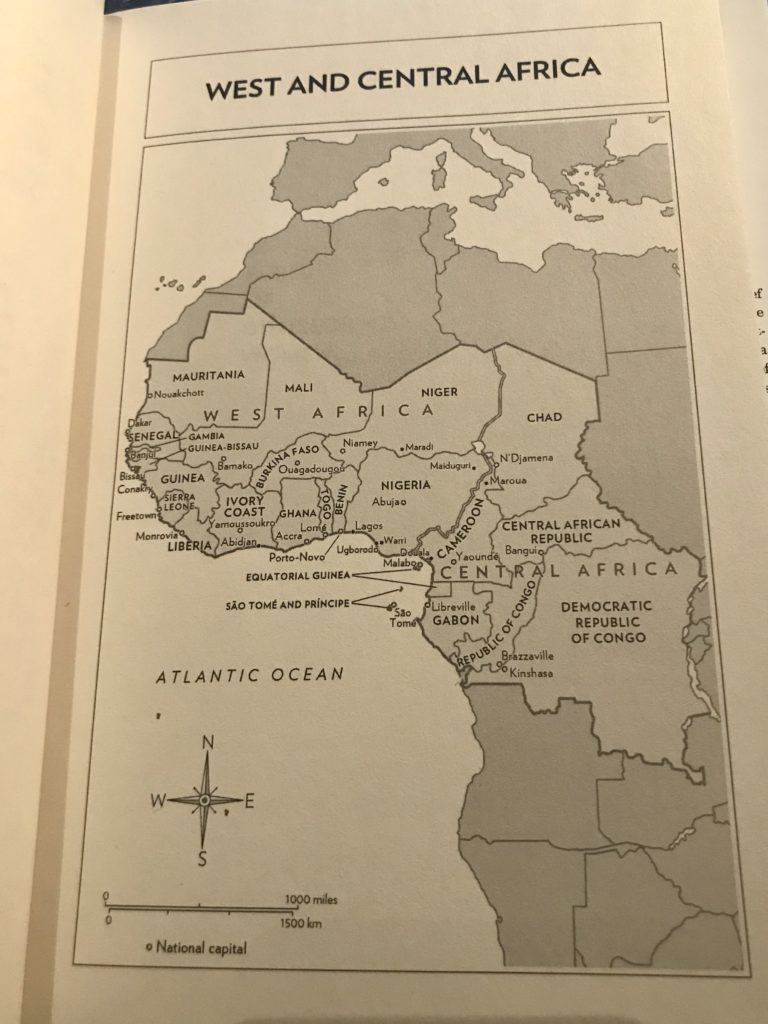

This memoir’s twist examines what it took to be a mother, wife, breadwinner and journalist as the Times’ West Africa Bureau Chief from 2015 TO 2019. I was intrigued with finding out more from Dionne about her theme of disobedience.

But before delving into her story, I asked her about the current global issue, COVID-19…

EYE: What kind of story are you pursuing with this pandemic now that you are back with your family living in Brooklyn, NY?

DIONNE: Right now I am assigned to the New York Times’ Politics Desk. What I’ve been doing are features on political divisions in America. And so what I’m looking at right now is how the virus is exacerbating, or not, that division.

I’m really interested in how the pandemic is going to shape our lives; what it’s doing to families and to communities; and how it’s going to shape our political opinions.

I think it’s really fascinating what lessons we’ll learn from this and how we’ll go forward.

EYE: How are you handling the pandemic personally?

DIONNE: My husband and I are both working equally while at home and take turns making dinner or wrangling the kids when one of us has an important call.

Like most people, we’ve learned to accept the low background hum of kids fighting or complaining and the dog barking in our virtual meetings and calls. Everyone is in the same boat right now.

EYE: What possessed you to up and leave New York five years ago and take the opportunity to be the West Africa Bureau Chief?

DIONNE: I’d always wanted to work abroad, and I really didn’t want to move out of New York City and to the suburbs, which my husband was pressuring us to do.

We were in a rut in our family life, and it seemed like a way to really shake things up, albeit a dramatic one for most people.

EYE: You titled your memoir In Pursuit of Disobedient Women. Would you define “disobedient?”

DIONNE: In this context, I was looking at women who literally defied orders of men in wartime, often women who defied expectations of a patriarchal society and women who are some of the most invisible members of societies that are run by governments and boardrooms and even their families.

They’re not decision makers, they’re not leaders of their families, and I wanted to see how they were upending societal expectations and just disobeying what was expected of them.

EYE: Can “disobedient” apply to you in any way?

DIONNE: I suppose that by being the main breadwinner while in West Africa I certainly upended expectations in a context where that was not the case for many local women or the majority of other Westerners who lived there.

I’m well aware of my privilege, however, and could never compare myself to the brave women I met who defied the societal expectations for them in so many clever ways.

EYE: Is there a particular story or a person that most exemplifies your “disobedient” woman?

DIONNE: I really was taken by one particular young woman in her early 20s named Zalika. She met her husband at a wedding as a teenager and married. She was in tailoring school, sewing school.

Her husband said, “Oh, you don’t need to pay for the classes, I’ll teach you how to sew.” He was a tailor like she wanted to be. She went along with it, dropped out of school, got married and left her family compound. Then he said basically, “Sorry, you’re not going to work. I’m the one who provides.”

And she was all by herself all day long. She was sick of it. She did not get to sew. One day she got sick and sent him out for medicine. He came back at the end of the day and forgotten to bring the medicine. I think anyone who is married or has a longtime partner can relate to the exasperation.

Also, she had often noticed when they did go out together, he was looking at other women. And she was really sick of it. What was amazing about this situation is she went to an Iman to get divorced. He wasn’t cheating on her, abusing her or hurting her in any way. But what she wanted was love.

And that was a new thing for women in this part of the world where girls are the most uneducated and girls are forcibly married. Young women don’t often have their own careers or are respected for their needs.

EYE: What was the most dangerous situation you witnessed in West Africa??

DIONNE: I saw women who had been strapped with suicide bombs who refused to carry out terrorists’ orders in northeastern Nigeria where Boko Haram and Islamic extremist group was operating.

These women were young and powerless and refused to kill anyone. It was really shocking that they had the bravery to fight one of the most dangerous terrorist groups in the world.

EYE: That must have been terrifying to cover. Is there a story that has had an international impact?

DIONNE: I reported about a civilian massacre and interviewed many people again in northeastern Nigeria where the military had rolled into town and accused everyone of supporting Boko Haram or being Boko Haram members.

The military lined up all the men and opened fire on all of them and then went to a neighboring village. I met with one man who had been shot several times, but somehow miraculously managed to survive.

Then I talked to other women who had seen what happened to their husbands. I think that story rattled the Nigerian government, and the U.N. wound up not including Nigeria on the Human Rights Commission. I was proud that the story got a lot of attention.

EYE: You have worked in very dangerous areas. Was there a craziest moment in any of your international reporting?

DIONNE: There were so many crazy moments. One was when I was in Syria riding in the back of a car and my fixer, a local journalist and friend, got a phone call. He just listened for a while and hung up.

He said, I think you better leave right now. Some sort of state security service, like the secret police, is warning me about you. What does that mean I wondered? He turned around and said they’re not going to shoot you, probably shoot at you.

So I decided that maybe it was time that I get out of town and we left.

EYE: How do you get the people that you interview in the very tense and horrible situations to trust you?

DIONNE: I feel like a lot of reporters forget to channel their own empathy. It is a very important reporting tool to understand your reactions as a human being and then use that in your reporting. Empathy can really help you ask good questions that can help people open up to you.

Also, a lot of people whom I talked to understood my role as a journalist and that I was a vehicle to get some help. These people had insanely traumatic experiences and no one had ever bothered to ask what happened. A lot of them hadn’t even told their mom or their husbands or anyone what had happened.

They understood I could be a messenger to get the word out and maybe someone could help or just even offer understanding of what they were going through.

EYE: What do you hope comes from writing this memoir?

DIONNE: We had hoped by my own experiences as a wife and mother that people could understand that regular people can move to places that we don’t often think about. But, what I wanted to convey the most was that Americans should be more focused on the African continent.

So many are so fixated on Europe or Asia. In these African countries, leaders are doing amazing work. This is a place that has a vibrant, rich, exciting culture and that these stories deserve to be listened to and acted upon.

EYE: What is it about journalism that intrigued you to pursue it as a career when you started as a crime reporter at the City News Bureau of Chicago?

DIONNE: I really love journalism. Where else can you just immerse yourself in one topic and learn everything you can about it in a short amount of time and then move on to something else?

I’ve had this range of beats where I’ve covered everything from government, local government to courts to police reporting to state government and politics.

I did a couple stints in Iraq during the war. I’ve covered earthquakes. It’s such a privilege to be on the inside of different things, talk to interesting people and then to get to explain what is going on.

I love to be able to shape the story, to think of a new idea, have people listen to you and to be that kind of conduit that helps people understand what’s going on in that world.

EYE: I was intrigued with the idea that you like to balance each tough story that you do with a hopeful one.

DIONNE: That was pretty much a direct response to criticism of Western reporters who go to the African continent and only write about famine and disease and war and malnutrition and all the bad things.

As a New York Times reporter, Presidents read your work, The State Department reads your work, the UN and so on. You can be a voice for the bad things going on maybe more than any other publication in the world.

I wanted to be hyper aware that I didn’t portray only violence. All these countries have poets, painters, art galleries and fancy restaurants. The horrible war with Boko Haram is confined to a very small part of the country. I just thought it was important to balance things out.

EYE: You became the breadwinner, your husband had taken on less responsibility for his job and you had your three young kids with you in your West Africa opportunity. How did you ultimately handle all of that?

DIONNE: Going running. Not like a fast runner or a far runner, though. I really like that headspace where you can just go out and be by yourself. I think when you when you’re a parent and you work and you’re in a relationship, you just need a little bit of time by yourself to think things through and to charge a little bit.

Open communication with everybody in the family, including the kids is really important as well as staying in touch with colleagues through WhatsApp groups. Those were lifelines.

EYE: What strengths do you personally count on for your successful writing, investigating and interviewing?

DIONNE: I like to pick out stories that can have resonance. In West Africa, writing the stories about social issues, about how women were treated or how what was expected of wives or even migration, how young men were often victims of migration. And no one really focused on that, even though they were part of families and breadwinners.

I don’t always get it right. But when you do, that’s a really nice feeling.

EYE: Thank you, Dionne, for your generous time and dedication to journalism. We look forward to reading more of your important reporting.

Since this post was published, Dionne received a Pulitzer Prize 5/4/20 as part of a New York Times’ team to report on Russia’s shadow wars. Here’s her story in that series.

Dionne’s social media:

- Website: dionnesearcey.com

- Facebook: dionne.searcey

- Twitter: @dionnesearcey

- Instagram: dionnesearcey

If you liked this article, you might be interested in our story on a Ugandan journalist:

Leave a Reply