By Patricia Caso/December 27, 2012

Photos from Martina Radwan

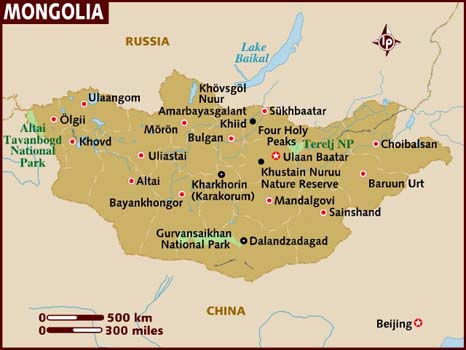

As a top notch cinematographer, Martina Radwan has captured many diverse images–from documentaries on world issues, to thrillers, to her first American short film on the color pink. Nothing grabbed her personal attention, though, until she was on assignment for UN-TV to document the isolated reindeer people and the plight of the street children in Mongolia.

“I chose cinematography because I wanted to tell stories of people who have no voice. With that skill I was hoping to bring on some change.” Martina Radwan

Martina interacted with Mongolian children so poor and desperate that she couldn’t forget them. She took one, in particular, under her wing–a wing she didn’t know she had. Now Martina travels over 6,300 miles from America at least three times a year to find them foster homes, facilitate their education, and set them on a path to self-sufficiency.

It is mindboggling to think Martina does all this on her own. She pours her spare time and money into her non-profit, Children of the Blue Sky. I was intrigued to find out more about these abandoned children and the woman who routinely travels a world away to help them…

EYE: How does a successful cinematographer decide to save Mongolian street children?

MARTINA: When I went on assignment to Mongolia in 2008, I was questioning how effective my job really was. I chose cinematography because I wanted to tell stories of people who have no voice. With that skill I was hoping to bring on some change.

For years I kept asking people for favors to open their house and their hearts for me and to allow me to participate in their lives. Then I would walk away and get a paycheck, but often there was no change. When I went to Mongolia I was in a real crisis, rethinking my career and that’s when I met Baaskaa.

“These kids create an underground culture using the central heating system to survive the brutal cold.”

EYE: How did Baaskaa, who was 16 then, turn your life around?

MARTINA: In 2008 UN-TV hired me to shoot a segment about the Mongolian homeless children. Parents are so poor and the living conditions are so miserable there that the children just leave, living by their wits on the violent streets.

The accepted estimated figure at that time for street children was 3,000-4,000 with around 400 sleeping on the streets year round, despite temperatures regularly dropping below —30 degrees C. To escape the cold many sought shelter in the underground heating systems, which made them known as “Manhole Children.”

We needed some visuals of children who had created their own underground culture, living in the manholes to survive. We asked if any kids would be willing to show us around. Baaskaa said, “I am willing; I have no family; it does not matter whether I am on TV or not.”

So Baaskaa and I ended up inside a manhole, and he was telling me a story. I had no idea what he was saying. I sat there listening to him talk for half an hour or more without understanding a single word.

EYE: How did you communicate with him when neither of you spoke a common language?

MARTINA: I think it’s because I understood nothing that it worked. I think when you understand, you go for the facts. I had nothing to go on, so I just watched him. That’s when I realized he is very special.

EYE: What did you see when you went down into the manhole?

MARTINA: Once I got myself oriented and got used to the smell and garbage, I realized this was someone’s home. There was a mattress, a clothesline, a candle, some sort of order in the chaos. It was very hot due to the steam pipes of the central heating system.

“I was never a believer in just giving money without improving skills, but because Baaskaa had a plan, I thought I could help him.”

EYE: Why did you decide to help him?

MARTINA: I could not get Baaskaa out of my mind. So I asked the Police Colonel Chodgov more about him. He said Baaksaa had a plan to live in the countryside and own a dairy farm. But he did not have the money to do that. So, to make money he wanted to work in mining or construction.

I decided I wanted to support him and his idea. I was never a believer in just giving money without improving conditions or helping to develop skills, but because Baaska had a plan, I thought I could help him. He could be independent, off the streets, and moving in a direction. Of course I was utterly naïve.

EYE: How did you help him?

MARTINA: After I returned home in March of 2008, I kept emailing, calling and asking about foster homes. I learned nobody wanted to take teenagers and he was 16. By May of 2008, I was back in Mongolia to help him.

With the aid of a wonderful woman translator, Selenge, and a few trusted people there, I finally found a foster home for Baaskaa, bought him a yurt (a tent house) and goats. The idea was that he would learn the traditional Mongolian job of herding. I was able to do this with my own money.

I also put him through vocational school. He learned the job of driving an excavation truck to make some money. However, since Mongolian training isn’t necessarily the same standard expected by Western companies that employ drivers, he’s had to get more training. Baaskaa also has no idea how to apply for jobs. So I am working on that!

“I decided to ask friends and colleagues for help and formed a very small organization.”

EYE: What makes you continue to help these children?

MARTINA: It took about $4,000 to get Baaskaa settled. It seemed like a little money for a huge effect. I thought I would do it again! I decided to ask friends and colleagues for help and formed a very small organization. Then, I went back to Mongolia and got a girl and another boy.

I knew no one wanted a girl. It was worse for a girl because everyone is afraid that a teenage girl will be getting pregnant, so no one wants to deal with her. My police friend pointed a girl out to me. Her name was Nasa.

EYE: How do you evaluate the families and keep track of these kids?

MARTINA: I move in with the kids for three days with the family. The family and kids get to know each other and they make the decision if they want to live with each other. I have six kids now in various stages of becoming independent. Nasa, the girl, is illiterate but the most successful.

She has two cows! I am working on her education. Without the help of Selenge, my translator with a huge heart, I would not be able to keep track of these kids while I am away. She delivers letters to them once a month and sends letters back.

For me, it means going to Mongolia several times a year, and staying for a month each time to push along progress and check on the families.

EYE: Did you have any idea what you were getting involved with?

MARTINA: None! The cultural differences are huge. Kids are seen as just small adults who fend for themselves. It’s a nomadic existence where everything depends on family ties.

I also did not know that this would become a lasting relationship. I just thought I wanted to help children. You don’t think these things through. But, for me, there was no question but to become involved.

EYE: You’ve said you embrace Mongolia with all its adversities and poverty. Why?

MARTINA: I love Mongolia because of its harshness. I went to Mongolia to shoot a segment on the reindeer people as well as the street children.

Travelling for three days, we only saw rolling hills, rivers, some trees, herding animals, cows, horses, camels and very few people. The beauty of the landscape was humbling, but it also gave me a feeling of belonging and connection. There is poetry to this emptiness and starkness. You can only respect the earth and understand that while our time is limited, the earth will survive, one way or the other. I guess I had a spiritual experience.

Mongolians love their country. They are very connected to their land and traditions, a connection we have lost. I guess I am a purist, and living out there in a a yurt made me wonder if all those things we do and have to make our life easier really improve our life.

Don’t get me wrong. I do not want to live in a yurt and milk my cow daily, but living out there without water or electricity were good reminders to think about what’s important and what’s not. Besides, Mongolians are extremely funny and laugh a lot amidst all this harshness.

EYE: Why don’t you expand your organization?

MARTINA: The idea is to help the ones I already identified to become independent. I see what works and what doesn’t. If I start expanding, I would deal with all the logistics and administrative stuff, not the kids themselves. It’s me they trust, not the system.

I am also trying to teach the children to help each other, to develop a sense of community. They see each other as siblings. They jokingly call Selenge their Mongolian mother and I am their American mother.

“I want the kids to become self-sufficient, think independently, and know their value as a human being…”

EYE: How do you manage financially?

MARTINA: Friends and people I meet through work give me donations. Filmmaker Astra Taylor and her talented indie musician husband, Jeff Mangum, whose website is Walking Wall of Words, attached my organization to his charitable donations and gives me $1 for every ticket sold. His last donation facilitated better conditions for Baaskaa.

EYE: What do you want for the children you rescue?

MARTINA: I want the kids to become self-sufficient, think independently, and know their value as a human being and be proud to be Mongolian. Right now they think they are third class because they are orphans, and Mongolia is not like the Western world in the movies.

EYE: Does it upset you that they would adopt Western ways?

MARTINA: Yes! I believe they should keep their culture. I had a long talk with Baaskaa about how important tradition is, that he must keep it, keep his identity and be proud. In fact he asked me to buy him a Mongolian hat to replace his hip hop look! He has since talked about educating other children about Mongolian life and traditions.

EYE: Why were you motivated to do this? It seems like a huge challenge…

MARTINA: I was on my own at 16 in Germany, growing up with very little guidance. I empathize with these kids. Over time I realized that what I am doing for them is what I hoped I would have had done for me. And I do think that people don’t just help out of the goodness of their hearts. There is always some motive–some reason relating to the human spirit–why you get involved.

EYE: As a cinematographer, do you ever look at your life as a movie of sorts?

MARTINA: Well, maybe not my life, but Baaskaa’s, yes! As a child in Germany, I always loved stories. I loved imagining things. I was incapable of expressing myself using language. But with my camera, my images speak.

“When I get frustrated, I just look at those kids’ faces. They are my joy…”

EYE: What are you most excited about so far in your journey with these kids?

MARTINA: No doubt, Baaskaa. He is doing so well. But, I need to bring him back to the U.S. so he can learn English. Although Nasa is totally illiterate, she is the most successful and independent. Happily, I finally found a teacher who relates to Nasa’s way of learning.

EYE: Doesn’t all this travel and communication over such a long distance just get too difficult?

MARTINA: When I get frustrated, I just look at those kids’ faces. They are my joy.

EYE: Martina, you are the tangible meaning of one person making a difference, one person at a time. Thank you for taking the time to talk with us in the midst of shooting a film and traveling back and forth to Mongolia. To learn more about Martina’s work, go to her website, Eternal Blue Sky of Mongolia.

###

Patricia Caso was a television producer and an executive producer for 15 years. She then freelanced and volunteered while raising two young men with her husband, Laurence. Now, Patricia has the wonderful opportunity to interview and write for The Women’s Eye. You can contact Patricia here.

Patricia Caso was a television producer and an executive producer for 15 years. She then freelanced and volunteered while raising two young men with her husband, Laurence. Now, Patricia has the wonderful opportunity to interview and write for The Women’s Eye. You can contact Patricia here.

Thank you for this article. Like Martina, I have such a heart for Mongolian teenagers and long to live there and to find more effective ways to help them. So it is with great interest I glean ideas from Martina’s activities. It is wonderful to see someone like her, using what is in her hands, her skills to reach out and make a difference. May she long continue her work and inspire more people to get involved. It is certainly worth considering what is really of value in this life, and Mongolia is a place so special, you can find the answers there. My husband and I both love the Mongolian culture, fun and sense of humour. It’s just such a shame that alcohol has such a terrible effect there.

Thank you for your comments. We are so grateful that Martina shared her story with The Women’s Eye. It will be so interesting to read about the fruits of Martina’s efforts with her rescued kids in the upcoming months…and years. Martina’s passion is to be admired, and as you said, is inspiring!

Martina is an amazing and inspiring woman! We all should follow her lead.

Thank you to both, the article and Martina. Sad thing is that nearly nobody believes the street children has a bright future, that is what I think but Marina trusts them to grow up as a good people. This trust is important to their life and it supports them and if someone ever give a trust to them at a time I think they will die to deserve it. They are very proud as a human being, I am damn sure about that.

Thank you to both, the article and Martina. Sad thing is that nearly nobody believes the street children has a bright future, that is what I think but Marina trusts them to grow up as a good people. This trust is important to their life and it supports them and if someone ever give a trust to them at a time I think they will die to deserve it. They are very proud as a human being, I am sure about that.

I have supported Martina and Children of the Blue Sky from the very beginning. It is unbelievable what she and Ayurra have accomplished over these few short years. From the moment she met Baaskaa she has persevered and made such a amazing difference in his life and the lives of others. Her commitment inspires us all to give back and to make a difference. Go Martina, Go!! Here’s to a 2013 filled with possibilities.

Martina is quietly making a huge difference in these children’s lives. I am in awe of her commitment.

Thank you for this wonderful article on Martina’s work. She demonstrates the positive impact one woman- with a little help from her friends- can have in directly improving the lives of young people. Undaunted by the cultural differences and geographic remoteness of Mongolia, Martina developed a mentoring strategy which provides educational and vocational support– as well as a lot of personal attention and love. As a result of her mentorship, much needed hope and self confidence has been instilled in young lives. Martina’s ongoing and expanding commitment to mentoring Mongolian children and young adults in need establish her as a role model. Congratulations, Martina.