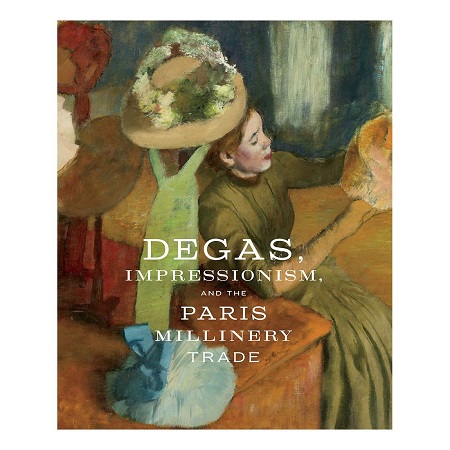

Degas Impressionism

By Wendy Verlaine/August 17, 2017

Photos Wendy Verlaine (@Verlainechirps)

Have you ever put on a hat and marveled at the transformation? If you think hats are an incidental accessory, then surely the sumptuous Degas exhibit at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco (through Sept. 24, 2017) will set you straight.

Degas is often associated with his ballet dancer paintings, and I was delighted to see work never before shown, and in context with a fashionable, turn of the century Paris. I found myself chatting with fellow women about hats from our past, and how those memories call up both humor and longing.

This exceptionally curated show of impressionist paintings and pastels, along with photographs and a running vintage video, is not only an homage to the millinery trade in Paris circa 1875 to 1914, but it includes the actual hats of this time period.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917) was deeply interested in the artistry and craft of women in the Paris millinery trade, as well as their plight of difficult working conditions. In the late 1890’s he produced a series of paintings and pastels featuring women absorbed in the creative activity of millinery.

Known to be enthralled every time he passed a Parisian high fashion millinery shop, it is easy to see how the mix of color, shape, textures and embellishments on hats led to Degas’ innovative uses of color and abstraction.

Born into a well-to-do family, he had a studio in close proximity to small independent millinery shops. He depicted the milliners’ skill, artistry and labor, and in this way, felt a kinship between their work and his. The impressionists visited the shops of the rue de la Paix often to view the hats by such prominent milliners as Caroline Reboux and Maison Virot, whose hats are featured in the show.

covered much of the face.

Paris in the mid 1800’s, considered the fashion capital at that time, had close to one thousand milliners. The varying hat designs and the role of the hat in society, which was de rigueur for both men and women, designated one’s wealth, social class, profession or marital status, as well as the wearers’ level of sophistication and taste. Over time millinery evolved from the individual artist working out of her home into an industry that employed hundreds of women.

and leaves on wire frame, 1910

Shopping, considered frivolous by some, came to be seen by most as an artistic endeavor for a woman, and a way to express her taste and independence. She enjoyed the inventive and personal aspect of designing her individuality. Degas focused his work on both consumers and laborers.

made her a celebrated designer

During the early 1880’s, masses of flowers appeared on spring and summer hats, and the show’s flowered examples are magnificent. A few women became fashion “super stars”, one of whom was Camille Marchais. She was renown for making artificial flowers, and had one of the most celebrated millinery shops in Paris. Her handmade flowers were so life-like they were hard to distinguish from living blossoms. Her skill made her the most sought after milliner of the day.

with metallic thread and artificial flowers, 1884

By the late 1890’s there was large demand for picture hats with wide brims supporting a mass of colorful blooms. The large brimmed hats were made to be worn asymmetrically on the head with the flowers delicately framing the wearer’s face. Hats had wire foundations covered with tulle, lace or other transparent materials.

Madame Virot, another celebrated designer who began her career as a milliner assistant, established her own house around 1860. Empress Eugenie soon became a client, and established Virot as one of the most sought after designers in Paris. Preeminent couturiers used her designs to complement their collections.

silk velvet and artificial roses, leaves and ferns, c. 1900

Not all women had the luxury of working out of their homes. An entire millinery industry sprung up in the mid 1800’s, and women often worked long hours in precarious conditions. Arsenic was used to preserve bird specimens, and mercury was used to soften the fur or hair of animals used in many designs.

Degas was interested in working trades, and many of his paintings depict the fatiguing and difficult working conditions. Low wages often forced some women to resort to other means of income, even prostitution. By the 1890’s support for better working hours and improved wages for women in French industry began to increase.

The Parisian hat industry also supported a massive international trade in exotic birds. France’s African colonies, Central and South America and Asia provided the feathers. The more exotic the feathers the more elevated the perception of the wearer’s social standing.

Plumage from French domestic birds, such as seagulls and owls, was also used. Some designs included whole stuffed birds or used wings and heads for ornamentation. This practice is thankfully illegal today.

During the 1870’s men’s style hats and dress wear, such as the bowler and riding clothes, began to change how women dressed. By the 1890’s women’s wardrobes took on more masculine style clothes and hats due to new forms of sporting activity such as cycling, riding or sailing. The straw boater was an example of a true unisex style, and was used for many outdoor activities.

riding hat and outfit/Degas c. 1910

For those of us who love looking at hats, and are secretly hoping this Paris trend will resurrect, your wish may come true. Paris fashion week 2017’s autumn-winter show claimed hats to be this year’s biggest trend. The catwalk was charged with headgear of all types, from Dior’s leather berets to glittery beanies, gaucho hats, borsalinos and wildly plummed fascinators. This may be the year your hat yearnings and wishes will come true.

Degas, Impressionism and the Millinery Trade at the Legion of Honor (@LegionofHonor), San Francisco is currently running through to September 24, 2017.

***

Wendy Verlaine is a San Francisco Bay Area freelance writer, jewelry designer and owner of Wendy Verlaine Design. Formally a San Francisco gallerist, she continues to stay closely connected to the art world.

Leave a Reply