By Patricia Caso/September 25, 2019

London-based journalist Zahra Hankir has covered Mid East and Arab political turmoil and violence throughout her career but admittedly not to the detriment of her safety. She was well aware that many women journalists, who live in and report from those diverse regions, face unbelievable odds to get the truth out yet Zahra was shocked to notice they received little credit. She stepped up to change that.

I was fascinated by information-gathering and dissemination, and the idea that the pursuit of truth and its reflection could be a profession. My obsession with journalism and the Arab world persisted over the years, and it culminated in this book.

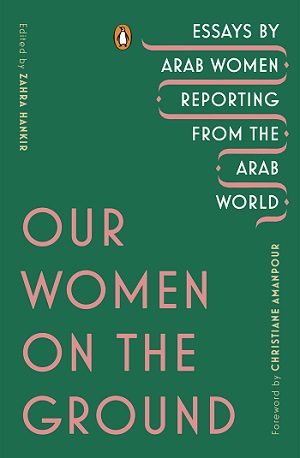

In Our Women on the Ground, Zahra asked 19 courageous reporters to share their powerful, unvarnished perspectives on their jobs and lives. Zahra took time with me to describe the importance of these journalists, known as sahafiya…

EYE: What is your goal in highlighting Arab and Mideastern women journalists?

ZAHRA: To give Arab women reporters a global platform so they can share their experiences of reporting from and living in the region from which they hail.

The Arab world and its people are so often seen as homogeneous, when the geographic area is intricately layered, and each woman and country and conflict carries unique truths.

This is also a long-overdue act of celebration and appreciation for the incredible work that these women have been doing on the ground over the decades, amidst seismic societal shifts and widespread displacement triggered by violent warfare and its crippling aftermath.

EYE: How dangerous is the work?

ZAHRA: Local Arab women often risk their lives at the frontlines as they cover their home or neighboring countries, and they haven’t historically been celebrated in this way and in these spaces. These women are not war correspondents or foreign reporters.

These journalists, correspondents and photographers are natives who tell different, more personal stories about conflict and its devastating consequences on their own people.

The women face steep and unique challenges that their Western counterparts do not. With all that in mind, their stories can’t help but be fascinating, and their work must be celebrated.

EYE: Why did you decide to compile their stories through personal essays and not interviews?

ZAHRA: I wanted the women in this book to tell their stories sans filters, and without any specific audience in mind, Western or otherwise. I acted as a guide, when I was needed, and I did indeed edit and curate the book and make editorial suggestions along the way.

I ultimately hoped that they would tell whatever story felt most poignant to them, and wanted them to be ready to tell that story. Looking at how the essays turned out — their range; the raw, intimate details they contain; and the honesty with which they were written — I do believe this was the right approach.

EYE: Were you surprised by any of the essays?

ZAHRA: It’s not that I didn’t expect the women to write openly and honestly, but I was, on occasion, knocked sideways by the extent to which they used their pens to open up and to excavate previously unearthed feelings.

I was in constant awe of their bravery, and their willingness to push boundaries without even intending to do so.

Zaina Erhaim, a Syrian journalist, for example, writes about how she had become so desensitized to violence in her hometown that one day, as she wiped blood off her car following a bombing at a nearby school, she called her friend and casually asked her what they should have for lunch that day.

Nada Bakri, a former journalist from Lebanon, wrote for the first time about the grief she endured after she lost her husband, Anthony Shadid, during the Arab Spring – there is no resolution in that chapter, no happy ending, no hopeful thread. The end of the essay is something of a gutpunch.

EYE: Why did you choose this format?

ZAHRA: It doesn’t follow what a traditional essay might look like. Indeed, this book does not sugarcoat. In many ways it reflects the situation in the Arab world today – resilience against a very real backdrop of tragedy and hopelessness.

I was also surprised by the extent to which I was emotionally invested in the book and the women’s stories.

I constantly felt guilty that I wasn’t doing enough, that I was living in privilege, editing these essays from the comfort of my home in North London while these women and millions of others in the region struggle with harrowing daily realities.

EYE: What did you find drives these women to continually face up to the sexism, violence, etc.?

ZAHRA: I would note it’s the desire to share and disseminate the truth that drives several of the women in the book. They have a profound understanding of how and why women are treated in the way that they are in their respective societies, and they fight misogyny by breaking into spaces they may not be welcome or expected in.

EYE: Is there a pattern among these women journalists in what they want to achieve and how they do it?

ZAHRA: The women were all unflinchingly committed to the act of journalism and the art of news gathering. Their tenacity, resourcefulness and resilience jump off the pages.

Perhaps this tenacity is best captured and expressed by Sudanese journalist and columnist Shamael el Noor, who never once doubts or reconsiders her career path, despite enduring grave challenges and constant threats to her safety.

She speaks poetically of journalism, not only as a profession, but as a way of life:

“I didn’t fully understand the value of my choices until after I faced all this danger and harassment–from the state, from tribesmen, and from Islamists. I have been a journalist for a decade now, and let me tell you what I have learned: this is what journalism should be, or else it shouldn’t be, at all.

Though these experiences have had high prices, they haven’t weakened or deterred me. I have no other option but to move forward, like the many brave journalists who face persecution. This is our destiny, and we remain ever devoted to it.’

EYE: Are there people or places these women can access that their male counterparts cannot?

ZAHRA: Women-dominated spaces and women-focused stories. For example, Amira Al-Sharif, a Yemeni photojournalist, enters the private homes of Yemeni women whose husbands and sons were lost to or engaged in war, to tell us stories of their strength and resilience.

Heba Shibani, a Libyan broadcast journalist, turns her attention to women’s rights by hosting a show that tackled major issues including the inability of Libyan women to pass their nationality on to their children.

EYE: CNN’s chief international anchor Christiane Amanpour said these women journalists “live and work in unrest and oppression.” How do they become journalists to begin with?

ZAHRA: These women were resourceful in overcoming many different challenges, including having to contend with families that opposed their career choices, sexist and misogynist workplaces, and threats of detention and arrest by the state.

In some cases they persisted with their ambitions behind their parents’ backs. Amira Al-Sharif snuck into local souks to take photos of Yemenis and documented university protests behind her father’s back.

She eventually won her family’s trust by persuading them, through her work, that this was a noble and necessary profession, and indeed the only one she wanted to pursue.

Egyptian journalist Eman Helal hid her bloodied clothing from her family after covering the fallout from the uprisings in Egypt. And she fought against the patriarchy by using her camera as a tool against sexual harassers. These are just two in a sea of examples.

EYE: What was your biggest challenge in editing this anthology?

ZAHRA: Ensuring an accurate portrayal of the region by diversifying the contributors to the best of my ability. Given space constraints, and the fact that we were dealing with a region containing 22 countries of more than 400 million. It was a somewhat impossible task to begin with.

I also wanted to include a range of time periods to give readers a broader perspective on political and social history, rather than just the Arab Spring.

While I’m pleased with how the book has turned out, I understand there are stories and conflicts and countries that were excluded. This is something I definitely lost sleep over, even though in some ways it was out of my control.

EYE: Did you always want a journalism career from a young age?

ZAHRA: Yes! I grew up in the United Kingdom, where I was born to Lebanese parents who had left the country during a drawn-out and devastating civil war. My parents constantly watched the news to follow up on what was unraveling in their — our — home country.

Landlines were frequently down, so they weren’t able to regularly speak to their families to stay abreast of the dire situation. So I grew up thinking of journalists as heroes, portals into another world who had the power to disseminate otherwise inaccessible information and who could shed light on faraway lands and complicated conflicts.

I was fascinated by information-gathering and dissemination and the idea that the pursuit of truth and its reflection could be a profession. My obsession with journalism and the Arab world persisted over the years, and I would say it culminated in this book.

EYE: What do you look for in a story before you commit to it?

ZAHRA: Tension, growth and/or change.

EYE: Do you have advice for new journalists?

ZAHRA: If you have a passion or a specific interest, then by all means, chase it, so long as you’re committed to upholding the highest journalistic standards. As a student at Columbia University, I was mentored by the late and great David Klatell.

I was hesitant when I pitched to him the subject for my thesis — private Islamic schooling in NYC — as I worried that I may appear biased or partial to covering my own community.

He encouraged me to write and report the story, and to not shy away from covering my community, people, home country or region, so long as I remained committed to reporting and writing ethically. It was priceless advice that has formed the backbone of my career.

EYE: What do you want the reader to take away from these essays?

ZAHRA: I hope readers will come away from Our Women on the Ground with a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the Middle East. Also that they will look more closely at who’s telling the stories of its countries and people, and seek out more diverse and specifically women’s voices.

Ultimately I hope readers will recognize the work that these women are doing as crucial to our full understanding of the Arab world, and celebrate them.

EYE: Finally, what is next for you?

ZAHRA: While more and more Arab women are being heard in this space, and more news rooms are employing and supporting locals, there’s much more to be done.

I’m passionate about amplifying the voices of Arab women and Arabs in general, and in advocating for more diverse newsrooms and more inclusive narratives, so I hope to embark on another project in this area. I’m just not yet sure what format it will take.

EYE: Thank you, Zahra, for your time and for your introductions to these journalists who are bringing real events of the Arab and Mideastern countries to the world. Continued success to you!

For more info about Zahra Hankir check out:

- Website: ZahraHankir.com

- Facebook: @zahrahankir

- Twitter: @zahrahankir

- Twitter Penguin Random House: @penguinrandomhouse

- Instagram: @zahrahankir

Thank you zahra,