By Patricia Caso/July 27, 2014

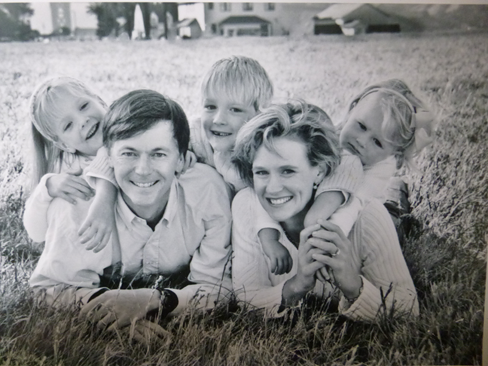

Photos: Courtesy of the Forbes Family

TWITTER: @SukeyForbes

Sukey Forbes struggled mightily in dealing with any parent’s unimaginable nightmare, the sudden death of her 6-year-old daughter. Charlotte had a rare genetic disease, malignant hypothermia. Her body could not cool itself down.

“I am really conscious every day of all the gifts small and large in our relationships. You get a real appreciation for what’s important when you are laid bare by unexpected hard times.” Sukey Forbes

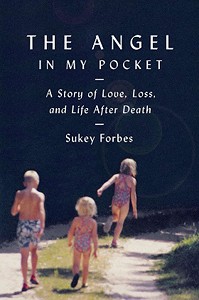

In Sukey’s memoir, The Angel In My Pocket–A Story of Love, Loss and Life After Death (Viking), she candidly and movingly addresses her process of grief. After reading her book and speaking with Sukey, I found not only a very comforting and instructive way of handling grief but also of handling life–when the rug is pulled out from under us…

EYE: Tell us about your daughter, Charlotte, and what life was like with her?

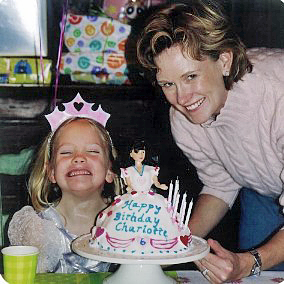

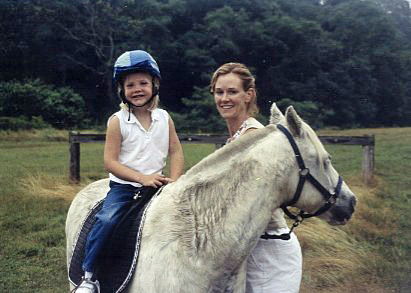

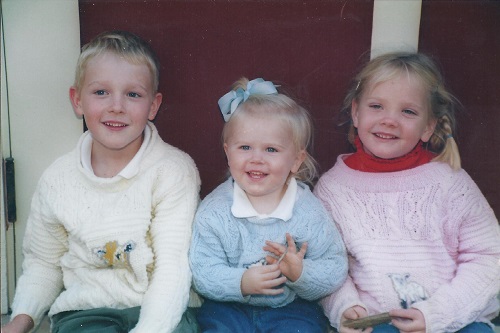

SUKEY: Charlotte was a middle child of three, full of personality. She really ruled the roost, dragging her older brother and younger sister around on all sorts of misadventures.

Charlotte was this lovely little blonde child with a devilish smile and big green eyes. She always had this little sardonic grin, always looking for the humor in things.

She had a great sense of fun and the absurd, very adventurous. Yet, Charlotte was absolutely a girl’s girl. She loved every princess out there and loved dressing up.

EYE: What made you feel so stuck after Charlotte died? How did you come to grips with her death?

SUKEY: I was stuck in the maternal instinct of needing to know where she was. It was as if you’re at a park and you lose your child. I was frantic, and I could not access my own grief until I had a sense of her physical location and her soul. That superseded anything.

I kept asking so many people, “Where is she?” like a character out of a Gothic novel in an existential crisis. Shortly after Charlotte died, someone I knew sent me a letter recounting a friend’s near death experience.

He had a glimpse of the afterlife in the presence of what he describes as “God,” a beautiful white light and acceptance. He didn’t want to come back. For some reason that shifted the tide. I clung to that evidence that Charlotte was in that clearly good place.

That was enough to set me on my path and quiet me down a little bit. I could settle into myself at that point, start to feel and process.

EYE: What do you mean you were unable to “access feelings of guilt?”

EYE: What do you mean you were unable to “access feelings of guilt?”

SUKEY: They were the more obvious feelings of grief, in terms of sorrow and anger. I was not able to access them. I felt like I was outside my body watching myself. Part of that is my cultural upbringing. In Forbes’ family fashion, we simply carried on as if nothing were the matter.

I was just stuck in my head. It felt like it was too much of a luxury for me to feel emotion before I knew she was, in fact, okay. It was also too frightening to start to feel. And, that may have been a stalling technique on my part.

EYE: Where did you find the strength to proceed and still care for your other two children and husband?

SUKEY: That’s where I drew my strength. I thought that the only thing worse than losing a child were if my surviving children lost their childhood as a result of that. Similarly, I was married to their father and I needed to be there for him as he needed to be there for me.

EYE: You kept a journal throughout this whole process. Why was that such an effective tool in your grieving and healing?

SUKEY: I have always been a journal keeper. Writing for me is the way of making sense of what was going on inside of me and out. And, for me, sitting quietly with the exercise of putting pen-to-paper frees up my thinking.

“I would add journaling as one of my top recommendations for anyone whose life has taken an unexpected turn, not just grief. Writing is a very powerful vehicle. Many of the answers to the questions that burn in us are deep inside of us.”

We just have to sit quietly, write and they will come out on the page. If we spend too much time looking outward and not examining inside we won’t have the ability to get those answers.

EYE: Mediums and clairvoyants figured in your process as well. How are you so comfortable with the spirit world?

SUKEY: We grew up in large old houses. There was a sense of spirits or ghosts. Many of my family members have personal ghost stories of some kind. While I didn’t give a whole lot of thought to the presence of ghosts, I just sort of generally believed that there was more than just concrete life and death.

When Charlotte died, I was placed in that position of having our life take an unexpected turn and I didn’t know how to proceed. When I began to look outside of myself for answers, I was very open-minded. We need to look inside in equal parts to looking outside of ourselves. And if we do too much of either, we get stuck.

This became a turning point for me. Henry James refers to it as an absorbing errand. He wrote, “True happiness, we are told, consists of getting out of one’s self….and to stay out you must have some absorbing errand.” Clairvoyants and mediums may not be the answer for others, but for me it resonated.

“It gave me in very concrete terms a validation that life and death are just steps along the continuum. Our loved ones are separated from us, but not gone.”

EYE: Will you explain how going to a medium gave you the final assurance that Charlotte was okay?

SUKEY: In the medium’s guided meditation, we got in an elevator and went several levels. For me it opened up onto a very broad field like the one Julie Andrews was on in The Sound of Music. It was a beautiful green grassy area and then from far, far away I saw Charlotte.

In an instant Charlotte was about an inch from my face shaking her head back and forth saying, “Hi Mummy!, Hi Mummy!, Hi Mummy!” in a playful sing-song way. I just knew that this was not my imagination. It was her.

It just felt so concretely that it was she who was visiting me. She was so okay! It was as if you picked up your child from a wonderful day at school and she came, threw her arms around you and said she had the best day and went on and on.

I began to weep. I was physically exhausted, puddling to the floor with relief, physically overwhelmed. I now knew she was okay and accessible.

EYE: What do you mean “accessible?”

SUKEY: I feel very much that in times of quiet, in times of need, that if I sit quietly and think about her, very similar to praying, she is like an angel or higher being who is hearing and helping and guiding on the other side. Charlotte is accessible.

EYE: The philosopher and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson had a lot to do with your process. He also is your great-great-great grandfather. How was he so integral in helping you?

SUKEY: He was important to me initially as a family member, not as a poet or the sage of comfort. When Charlotte died, I looked to my family first for a sense of the structure of how they had handled loss.

Ralph Waldo Emerson had lost his 6-year-old son to a fever. I lost my 6-year-old daughter to a fever, so that felt to me like a very powerful connection.

I was aware that Emerson’s last words were, “That boy. That beautiful boy.” That had always haunted me and been curious to me. He was a seeker. He had lots of questions. He went to his wife’s crypt a year after she died, opened the door, and said, “I just had to see.”

I identified with that desire to have more understanding of what had happened, what had become of the flesh and blood. I came upon his quote, “ Sorrow makes us all children again, destroys all differences of intellect, the wisest know nothing.”

I thought, oh my gosh, we all do become children again when we are stripped emotionally from loss; we have to find our way again emotionally and build ourselves back up.

Like the family beliefs I grew up with, Emerson also wrote about self-reliance, God’s presence in Nature and the divinity inside each one of us.

“He also described his fears and inability to feel. ‘I chiefly grieve that I cannot grieve.’ There were a lot of parallels that kept circling me back to him as a strong force in my own life.’

EYE: What did you find were the most important steps in your healing?

SUKEY: Writing for sure. Next, open-mindedness to other ways of thinking, a general curiosity to explore other possibilities. Our natural inclination is to circle in when we are in pain.

Opening our hearts and minds, which is very hard to do, is critical to the healing process. I am also a big believer in reading to discover a potential path. After that, would be physical movement.

Grief and emotion stores itself inside our body at the cellular level. We can’t think and feel our way through grief, we have to move it, literally move it through our system. I was very aware of being unable to take a full breath. I still feel that tightening at emotional times. Exercise and movement can move pain and emotion out of the body.

EYE: Was there an obvious obstacle to your healing as you look back?

SUKEY: I was afraid I would never emerge. Had I known more that this was a process I would move through, that I could be okay and be a better person if I wanted to, then it would have been easier to slide into that abyss for awhile.

We all have times when we feel awful. We feel like it will be endless. But I was so fearful of falling off that cliff and never landing, never emerging, that made it very difficult to process.

EYE: Why did you ultimately write a memoir about such a personal tragedy and struggle?

SUKEY: We need more examples of people who are resilient, who are courageous about moving through it and writing about it. The grief is part of the story but it is the ending that sets it apart.

I want people to take away the comfortable resting spot. We all get there in different ways, yet there are common ways to get through it.

People cannot put their nose to the grindstone and ignore the pain. Like Winston Churchill said, “When you are going through hell, keep on going.” We do get through it if we want to. That is the overreaching message in my book.

EYE: What personally surprised you on the other side of this process?

SUKEY: I am a much better person having gone through this, although I didn’t dislike myself before. My heart has grown; my capacity for curiosity and empathy and understanding is greater. My life is richer and more abundant in all directions.

I am really conscious every day of all the gifts small and large in our relationships. You get a real appreciation for what’s important when you are laid bare by unexpected hard times. I will say I would give all that up in a nano-second if I could have my daughter back. But, I can’t bargain her back, much as I’d like to.

“So, I am deeply appreciative of the wisdom and the capacity of being a human being that I’ve gotten out of the process. I am happy.”

EYE: Thank you for making time to share lessons from your personal loss with me. Certainly there will be many people who will benefit from your memoir. More resources and information can be found on Sukey’s website.

You can buy The Angel In My Pocket here.

###

Leave a Reply